Elena discovers that Sasha gets involved in those increasingly dangerous gang wars and wants to send him to a good university, lest he be drafted by the army or end up rotting in prison for petty crime. She pleads with Vladimir for the money, but because Sergei and his family are Elena’s children from a previous marriage, he will not help them. One day, chance intervenes and there is an opportunity for Elena to get the money to help her son’s family, after all. The means by which she can do so, however, are rather unsettling and constitute a moral dilemma that vaguely recalls those other purveyors of Russian misery and ethical debate, Tolstoy and Dovstoevsky. The results are chilling.

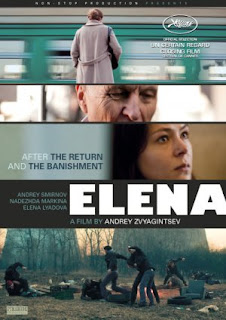

Andrei Zvyagintsev’s remarkable film Elena played out of competition at Cannes this year, where it received the Special Jury Prize in the Un Certain Regard section for non-competing films. Regarded as an important landmark in Russian film, it’s easy to see why. Elena is a modern parable and an analysis on how Russian society has been evolving and may evolve in the future. In this film, we see four generations of the same country represented: the old guard who have siphoned off most of the wealth and hoarded it for themselves once the Iron Curtain fell; the aging baby boomers who constitute the professional working class; the Gen X-ers who came of age in the dawn of Russian capitalism and who are now slave to rampant sloth and alcoholism; and the post-Soviet youth who couldn’t have ever fathomed standing in bread lines. Taken as sociopolitical allegory, the film traces the flow and redistribution of wealth in contemporary Russia, and who will inherit and become the nation as the class divide ever widens between the mega-wealthy and the destitute who survive on the average income of $600 a month. It’s not difficult to see, in the end, how the new generation of “spoiled bratskis” came about, the ones whose obscene displays of nouveau riche through wild spending and frequent trips to GUM and TSUM obscure the country’s true state from international headlines.

That Elena takes place in a completely nondescript city with no identifying markers just might make this contemporary Russia’s answer to American Beauty: it speaks to larger social problems that decay the system. And yet Zvyagintsev bookends the film with contrasting images showing that life will somehow go on, even if it continues through misbegotten means and questionable choices. Anchoring the film is veteran Russian actress Nadezhda Markina, in a remarkable performance where she doesn’t say much, but communicates so much with body language and subtle movements, like a great silent film actress. There’s also an elegant score by Phillip Glass, one that flows throughout and lends the film an appropriately chilly demeanour.

That Elena takes place in a completely nondescript city with no identifying markers just might make this contemporary Russia’s answer to American Beauty: it speaks to larger social problems that decay the system. And yet Zvyagintsev bookends the film with contrasting images showing that life will somehow go on, even if it continues through misbegotten means and questionable choices. Anchoring the film is veteran Russian actress Nadezhda Markina, in a remarkable performance where she doesn’t say much, but communicates so much with body language and subtle movements, like a great silent film actress. There’s also an elegant score by Phillip Glass, one that flows throughout and lends the film an appropriately chilly demeanour.Elena played to capacity crowds at the Vancouver International Film Festival. The reviews have been dazzling, and it has already caused a sensation in Russia not just for its content, but also for its omission as the Federation’s official entry for the Best Foreign Film Oscar. Given Elena’s rapturous reception at film festivals the world over, this is indeed a shame.